Before Instagram feeds were flooded with beige aesthetics and cactus flat lays, Georgia O’Keeffe was already out there in the New Mexico desert living it. She didn’t need filters or mood boards; the high priestess of desert drama and petal power was the aesthetic. Her clean lines, color harmony, and unapologetic independence made her the original minimalist long before minimalism started charging $300 for a neutral-toned sweater.

Born in 1887, O’Keeffe grew up on a dairy farm in Wisconsin, but her imagination outpaced her surroundings. By the time the art world caught up, she’d already reinvented what it meant to see. When everyone else was painting proper portraits and pastoral scenes, Georgia was zooming in…way in…on flowers, bones, and landscapes that blurred the line between realism and dreamscape.

“Nobody sees a flower – really – it is so small it takes time – we haven’t time – and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time.”

― Georgia O’Keeffe

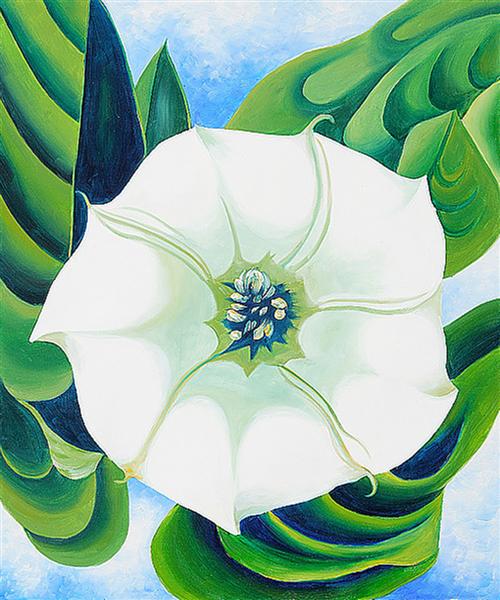

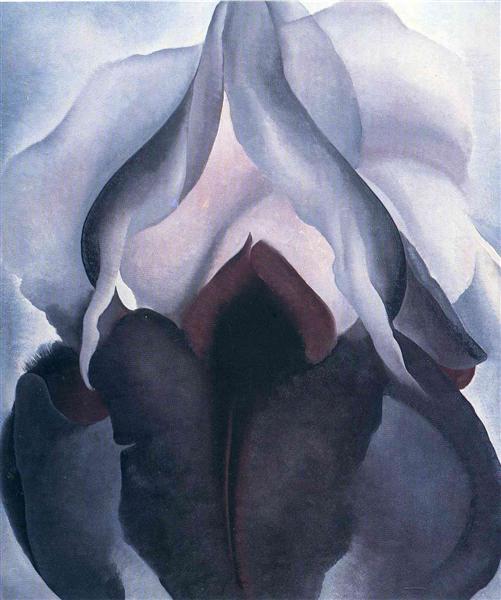

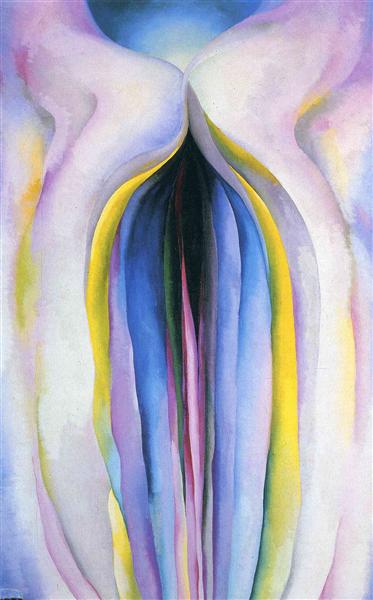

The Flower Scandal: Art or Something… Else?

Let’s talk about the elephant, or rather, the orchid, in the room. O’Keeffe’s close-up flower paintings caused quite a stir. Critics, mostly men with Freudian overconfidence, insisted her work was “symbolic” of female anatomy. Georgia’s response? A confident, desert-dry eye roll.

“I made you take time to look at what I saw,” she said, “and when you took time to really notice my flowers, you hung all your own associations with flowers on my flower.” Translation: that’s on you, buddy.

The truth is, O’Keeffe wasn’t painting innuendos; she was painting intensity. She wanted people to look, not just glance. To see the world’s details with reverence and curiosity. If her flowers made you feel something… well, that’s the power of good art, isn’t it?

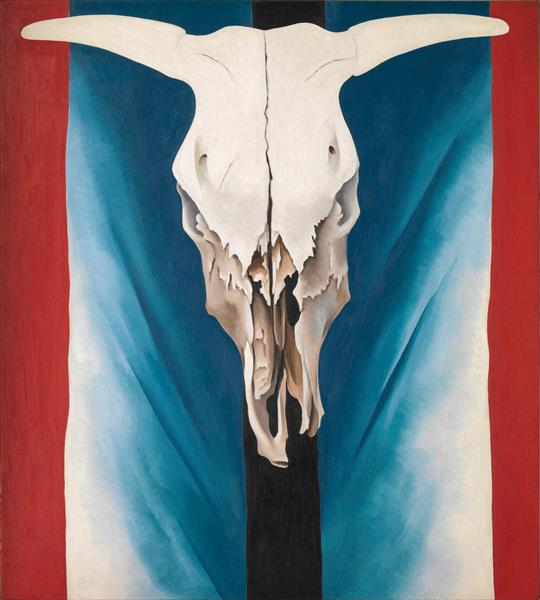

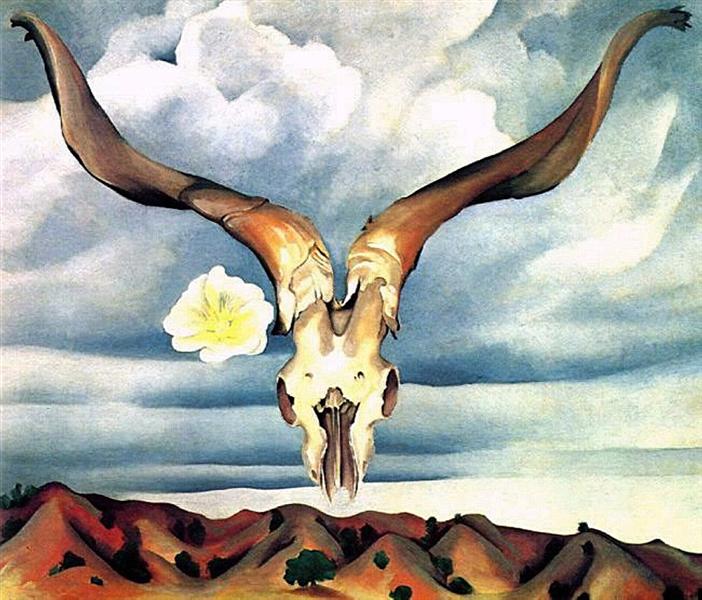

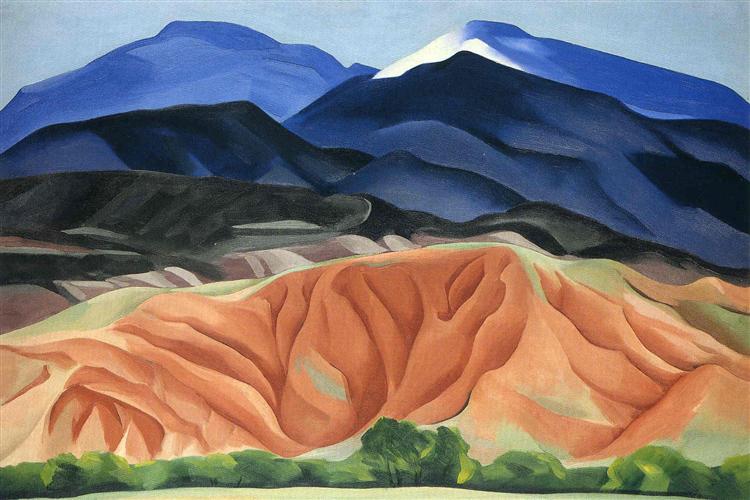

Bones, Deserts, and Existential Vibes

When she moved to New Mexico in the 1930s, O’Keeffe’s art hit another level. The endless desert wasn’t empty; it was alive, pulsing with light and mystery. Cow skulls, weathered cliffs, and bleached bones became her muses. While others saw desolation, Georgia saw design, rhythm, and energy.

“I’ve been absolutely terrified every moment of my life and I’ve never let it keep me from doing a single thing that I wanted to do.”

― Georgia O’Keefe

Her paintings turned isolation into poetry. You could almost feel the hot wind and hear the silence. Each bone, each canyon, each curve was a love letter to the landscape’s soul. In an age obsessed with skyscrapers and speed, she reminded the world that stillness was its own revolution.

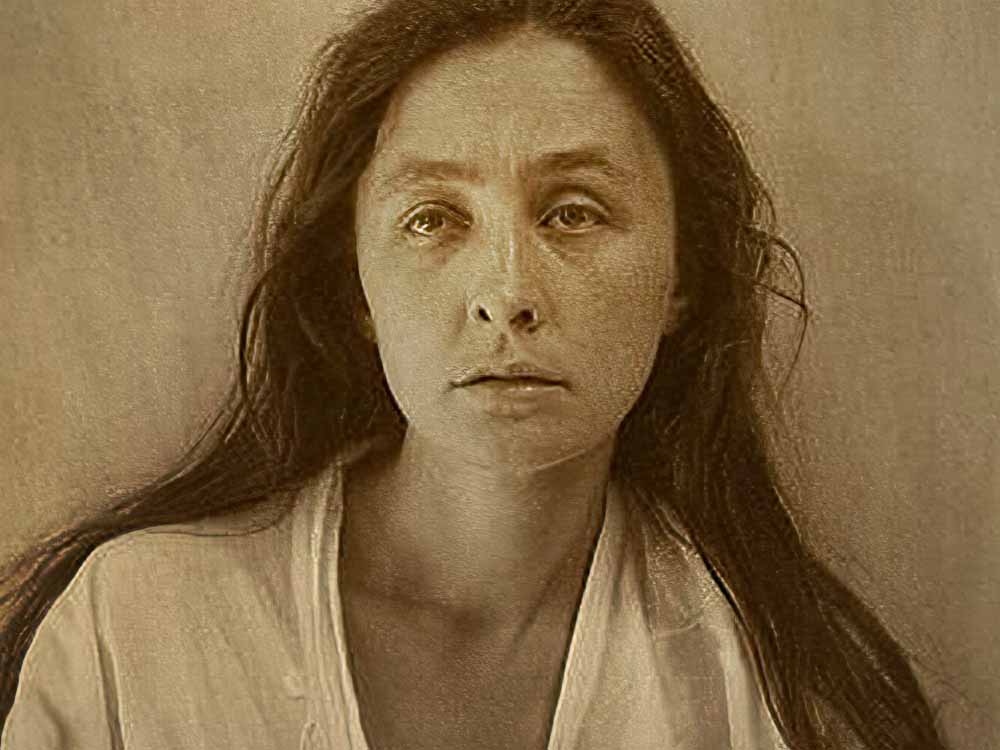

The Woman, The Myth, The Icon

Georgia O’Keeffe didn’t just paint; she built a brand before branding was a concept. A wide-brimmed hat, black clothing, and a desert backdrop, she curated her image as sharply as she composed her canvases. A true icon of artistic self-reliance, she lived on her own terms in a world that expected women to shrink. She expanded instead.

“I have already settled it for myself so flattery and criticism go down the same drain and I am quite free.”

― Georgia O’Keefe

Why Georgia Still Matters (and Always Will)

O’Keeffe’s art feels as fresh today as it did nearly a century ago because it speaks to something eternal: the courage to see differently. In an attention-span economy, her slow, meditative vision is radical.

So next time you scroll past a flower photo… pause. Zoom in. Notice the texture, the shadow, the quiet rebellion of beauty. That’s O’Keeffe’s legacy.

Channel your inner Georgia. Take your phone, your brush, your camera, whatever your medium, and look closer. The world’s beauty isn’t hiding; it’s just waiting for you to really see it.

Looking to explore more art genres? Head over to JoeLatimer.com for a multidisciplinary, visually stunning experience. ☮️❤️🎨

Enjoy this blog? Please help spread the word via: