In the early-to-mid stages of the art student’s career, the focus of study eventually falls on an art movement nearly entirely unknown to the vast majority of laypeople. It is almost universally impossible to understand for virtually everyone. Its unexplainably is at both times the only source of its appeal and the main reason why most people don’t really like it.

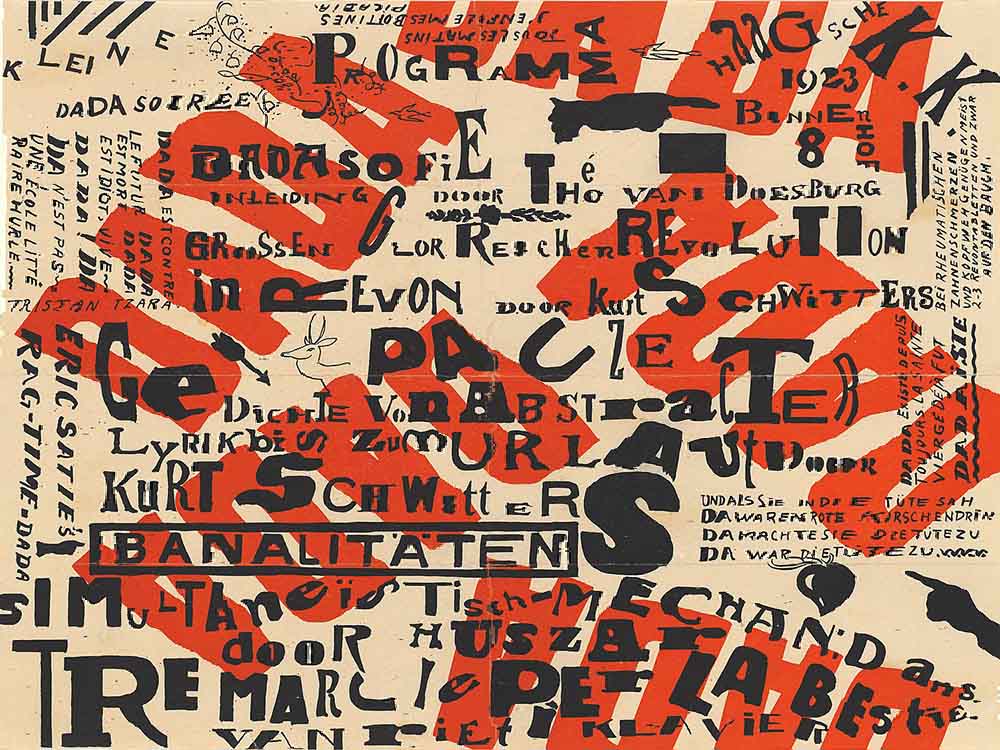

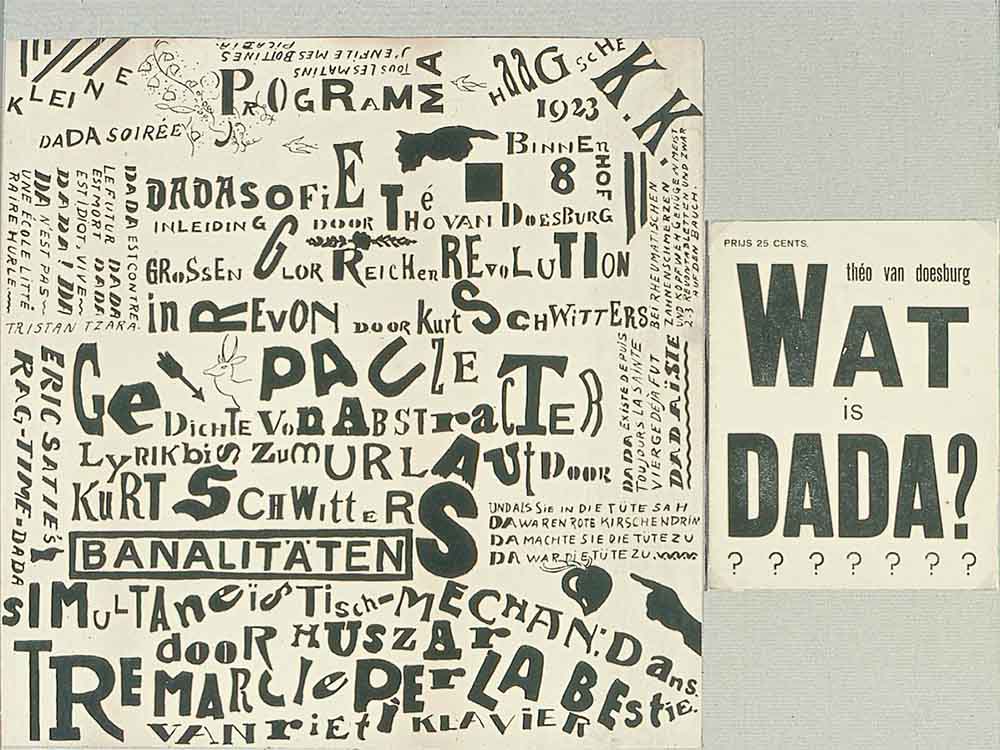

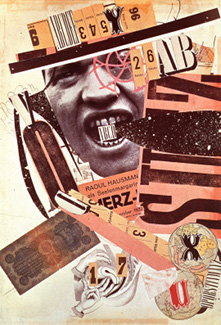

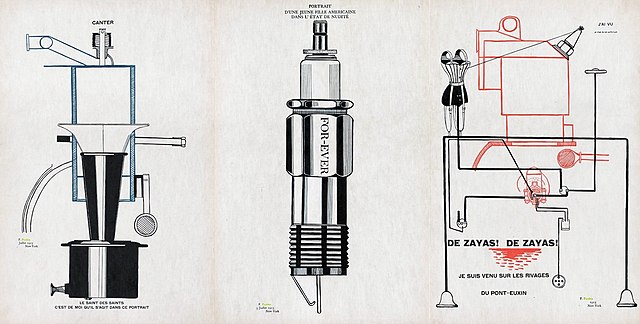

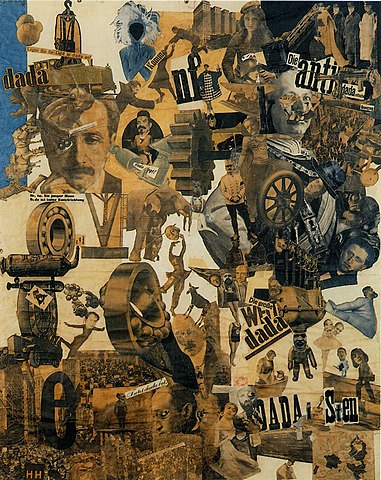

Dada is an avant-garde art movement in the early 20th century characterized by a rejection of classical aesthetics and rationality, and utilization of nonsensical themes to communicate criticism of modern society. It was contemporary with other radical new art forms including Expressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, and Surrealism. However, what made Dada unique among these is that while these other avant-garde arts were part of a movement that questioned the narrow-mindedness of what society would consider aesthetically pleasing, Dada instead questioned the very concept of aesthetics itself.

You’re probably asking, “What the heck does that even mean?”

Maybe a better way to explain is to show, not tell. This is Dada. There really is no more quintessential example of peak Dada than Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain. This fascinating art piece was, materially speaking, nothing more than a urinal turned on its back. I say ‘was’ because the original was lost (presumably because to most people it would just appear like garbage meant for a landfill and not a deliberately created work of art). This was one of Duchamp’s ‘ready-made’ art, which is essentially art created out of an everyday object that is minimally altered. Marcel Duchamp made dozens of these, which included putting a bicycle wheel on a chair, or a ball of twine between two plates.

“I have forced myself to contradict myself in order to avoid conforming to my own taste.”

―Marcel Duchamp

In a way Dada was very self-referential, you could almost compare it to memes. The name of Dada in and of itself is Dada. While there is no consensus on the origin of the name Dada, there are a few popular theories. For example, one origin story is that it’s from the Romanian word for “yes”, such that Dada is sort of like the way in English someone would say “yeah yeah” in an apathetic or sarcastic tone. Alternatively, it could be from the French phrase, «c’est mon dada» meaning “it’s my hobby”, as it’s possible that the name was decided at random by a group of artists in Zurich by stabbing a French-German dictionary with a paper-knife and picking whichever word the tip of the knife landed on. One interesting thought to consider is that by becoming a popular art movement, Dada eventually became exactly the thing it was originally created to mock.

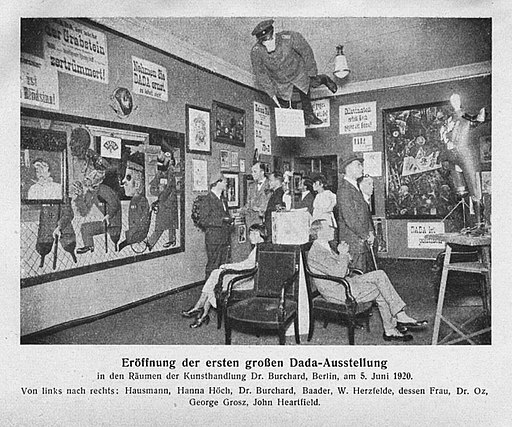

Well, then what happened to Dada? That could probably be best explained by giving some context for the type of world there was at the time. In fact, Dada was just a small part of a much larger social and political movement based on that building up of anger towards the growing autocratic elements in Europe in the immediate aftermath of World War I.

“Tradition is the great misleader because it’s too easy to follow what has already been done – even though you may think you’re giving it a kick. I was really trying to invent, instead of merely expressing myself.”

―Marcel Duchamp

The entire world at this point, but Europe in particular, was in the throes of political chaos where the last remnants of the old system of Monarchy were losing influence or being overthrown entirely, while Fascists and Anarchists engaged in open violence in the streets. As this era drew to a close and World War II began, Dada quickly faded away from the popular consciousness for a few reasons. First, many Dada artists were German, and due to the Nazi regime they either stopped making the banned art for fear of death, or in fact were simply imprisoned or executed. Along with other radical art forms, the Nazis called it “degenerate art” and would display it alongside arrogantly unintelligent and brutish criticism. The second reason would be that post-World War II was the beginning of a new and exciting era of optimism that simply didn’t have a market for something so aggressively strange and often depressing. But that’s not to say that there were absolutely no lasting effects of the Dada movement beyond the 50s, in fact, you can see the legacy of Dada even today.

Consider the much-criticized and generally disliked performance art of Yoko Ono, whose nails-on-chalkboard ‘singing’ is a very strong rejection of auditory aesthetics, similar to the earliest Dada works that bravely challenged the very concept of things needing to be pleasing for anyone. There is no doubt that Ono’s shrill harpy-like shrieks and groaning walrus mating calls are intended to communicate to everyone in earshot precisely two things: first, that our collective understanding of what is pleasurable to hear is dictated by an immaterial and arbitrary zeitgeist; and second, that this undefinable and anti-logically originating code of aesthetics deserves to not just questioned but insulted. Unfortunately, this message is totally lost in the noise, and instead of questioning why they like what they like and dislike what they dislike, people end up asking, “Are my ears bleeding?”

“I speak only of myself since I do not wish to convince, I have no right to drag others into my river, I oblige no one to follow me and everybody practices his art in his own way.”

―Tristan Tzara “Dada Manifesto 1918”

There are similarities between Dada and some other things that we openly accept today. While it does not in any way originate from Dada, at least not directly, there is a humorous hobby in Japan called Chindogu, which literally means ‘unusual tool’. The objective is to take a simple everyday object and modify it to be a bizarre tool that solves a very specific and relatable problem, but would cause other problems because of the nature of its impracticality. It’s a very gentle mockery of the idea that things should have some kind of relatable purpose or realistic functionality.

So what do you think? Do you think Dada is just a bunch of garbage, or is there something that’s really cool about it? Do you see Dada-like elements in the art scene today? Do you think most people like avant-garde or do you think most people prefer something more commercially marketable? Please leave your thoughts in the comments below!

Looking to explore more art genres? Head over to JoeLatimer.com for a multidisciplinary, visually stunning experience. ☮️❤️🎨

Enjoy this blog? Please help spread the word via: